A farmer without a market is like a crop without water — doomed. This fact is nothing new for modern growers, who must develop marketing plans that are proactive, comprehensive, and diversified. One common feature of such plans is contract farming, also known as “outgrower schemes” — a type of mutually-beneficial partnership between producers and agribusinesses that can provide greater stability and production risk management to agricultural value chains.

With 49% of US livestock production and nearly 20% of crops grown under contract, the importance of contract production to supply chains, food security and farm incomes cannot be understated. Large and small farms alike rely on contractual arrangements to market their produce, though small-scale farmers are especially reliant on contracts, particularly in developing countries where agricultural production may form the basis of the local economy.

Table of Contents

What is Contract Farming?

Understood generally as a type of vertical coordination within agricultural supply chains — a prior agreement between a producer and a buyer — contract farming schemes can take many forms. Whether between a farmer-cooperative and supermarket, between individual farmers and seed companies, or even between one farmer and another farmer, the scope and size of contract farming vary considerably on a case-by-case basis.

Typically, a contract farmer agrees to deliver a certain quantity of a crop to a buyer according to certain logistical and quality standards, in return receiving either an assured market price, shared risk, and/or a degree of agronomic support (e.g. inputs, advice, transportation, access to capital, etc.)

The USDA identifies two major types of contracts, marketing contracts and production contracts, though there are many other forms that contracts take throughout the world, such as nucleus estate contracts and custom farming.

- Marketing contracts refer to buyer-grower agreements that define a price and an outlet for a contracted crop prior to harvest. In this model, most management decisions, farming activities, and thus production risks remain with the growers, who technically retain ownership of the product; however, market price risk is shared with the contractor. Marketing contracts are an increasingly popular tool among younger farmers with diversified marketing strategies, with corn and soy growers comprising 60% of all marketing contracts in the US.

- Production contracts, by contrast, refer to arrangements that specify the quality, quantity, and delivery requirements of a contracted crop, in addition to any production guidelines, inputs, technical advice and extension services provided to a grower by the buyer. In these agreements, buyers and growers share the marketing and production risks, though the contract terms are often dominated by the contractor. This type of centralized model is common for crops like tobacco, cotton, sugar cane, banana, livestock, and tea.

- Nucleus estate contracts are common in developing countries like Ghana and Indonesia where smallholder farmers form the basis of the agricultural sector. These contracts are often employed in the production of high-value agricultural commodities such as rubber and oil palm, whose high establishment costs may have otherwise constituted a barrier to entry to small-scale growers. The nucleus estate model is comprised of a plantation, with the “nucleus” or center of the plantation operated by the company, and outgrowths of the estate (i.e. “plasma”) operated by the smallholder farmers themselves, often on their own land. Although this model has contributed to rural development and the dissemination of new technology, care must be taken during negotiations to ensure equitable contract terms.

- Alternative contractual models abound throughout agriculture; for example, farmers may contract other farmers to perform various activities such as tillage, soil amendment, seeding, harvesting, or brush-hogging on their land. Also known as “custom farming,” this arrangement allows contract farmers working on multiple parcels to benefit from economies of scale.

Contracting Farmers

Pros and Cons of Contract Farming

Before considering contract farming, farmers should be mindful of the advantages and disadvantages they may face as contracted grower.

Some of the benefits of contract farming include:

- An assured market for crops with a pre-defined market price

- Diversified farm income

- Shared marketing and production risks

- Reduced transaction costs

- Greater access to capital investments

- Transmission of new technology and agronomic advisory services

- Vertical coordination allows the resolution of market failures

While proponents point to the positive impacts of contract farming, identifying case studies demonstrating 25%-75% higher incomes and more stable rural livelihoods for contracted growers (Minot 2015), critics of contract farming, by the same token, point to case studies in which contract terms and incentives disadvantage growers, leading to land losses, large debt burdens for contract farmers, reduced animal welfare, and sustainability challenges.

Downsides of contract farming might include:

- The need for specialized inputs, equipment, or infrastructure, possibly leads to cycles of debt

- Less flexibility in production practices

- Less control over marketing decisions

- Failure to meet quality standards outlined in contract terms, leading to lower prices

- Contract terms favoring the buyer

In the post-colonial developing world — for example, in Kenya, Zimbabwe and other nations in Sub-Saharan Africa — governments have restructured their economies away from private, corporate, and state-owned plantations in favor of contract farming. This shift has in large part been facilitated by partnerships between NGO’s/IGO’s such as the World Bank, private sector actors, and governments. This global trend towards contract farming presents both opportunities and challenges for farmers, though resources for designing and identifying contracts prioritizing fairness and sustainability can be found here.

How To Start Contract Farming In The US?

In light of the growing popularity of contract farming, growers seeking to diversify their operations might be interested in learning more about whether contracting is the right fit for them.

Interested farmers must first decide the type of buyer with whom they would like to do business, though large firms with capital-intensive operations are the most common type of buyer. Food processors, input companies, supermarkets, and wholesale distributors across a range of commodities — from berries to beer, from grain to oil palm, from corn and soy to livestock — seek out contract growers to fill gaps in their supply chain, given their need for a steady and reliable flow of raw materials.

Interested farmers can seek out contract opportunities via local cooperatives, farmer organizations, and extension offices, though in some cases, farmers can approach firms directly to start contracting.

Like any business decision, signing a contract requires a thorough analysis not only of any costs, returns, or legal obligations on the grower’s end but also of best- and worst-case scenarios (e.g. natural disaster) and the implications for the contract.

Contracts are legally binding agreements, meaning farmers must assess every outlined term and condition before signing their name on the dotted line, analyzing any stipulations regarding crop ownership, crop quality conditions, payment terms, contract length, intellectual property rights, and many, many more. Depending on the farm’s size and farmer’s income, contract farming may or may not be right for you.

Using FMS To Manage Contracts and Finances

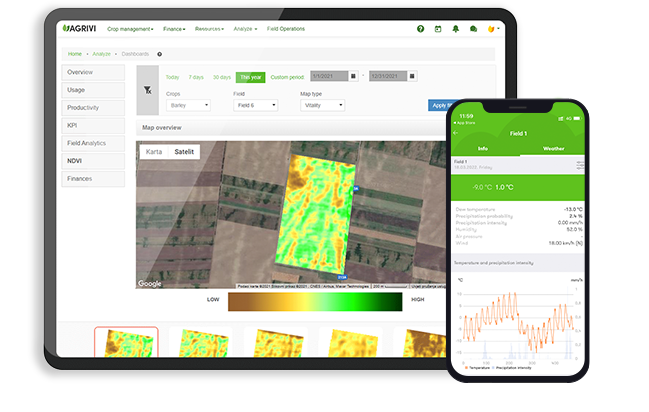

Farm management software (FMS) platforms like AGRIVI help growers manage the complexity of their operations, simplifying and centralizing not only crop management data but also marketing and finance data. With a cooperative platform designed for contract management — not to mention multiple budgeting tools, cash flow monitoring, expense, and sales tracking, and unlimited cloud-powered document storage — buyers and growers alike can quickly and easily assess important production deadlines, contract obligations, and costs and returns in one central place. With built-in communication channels and agronomic advisory tools, moreover, managing a network of buyers or a network of growers has never been easier.

Given the global prevalence and transnational nature of contract farming, growers and buyers alike need an adaptable FMS tool that features multiple currencies, units of measure, and languages. Featuring 15+ languages and used in over 100 countries worldwide, AGRIVI is the one-stop shop for growers, food processors, input companies, and agronomic advisors whose global footprints demand a global FMS.