Frost is the coating or deposit of ice that forms when outside surface temperatures past the dew point. It appears as fragile white crystals or frozen dew drops near the ground.

Frost is most common in low-lying areas. Warm air rises, and cool air sinks—cool air is denser than warm air. That means there are usually more water molecules in cool air than in warm air. As cool air collects in valleys, frost forms. It usually forms at night, when the air temperature is cooler. Once the sun rises and warms the air around the frosted object, the frost melts quickly.

Low spring temperatures can cause significant damage to farm and fruit crops by damaging the developing fruit buds causing significant economic loss to growers. Managing the risk of frost damage begins before the crop has even been planted by selecting a site that optimizes cold air movement and selecting cultivars that are appropriate for the region. When making decisions about how to protect a crop against frost damage, it is essential to understand the different types of frost and how conditions will influence which protective measure to use.

There are different types of frost:

- Radiation frost (hoarfrost) – frost in the form of tiny ice crystals that usually shows up on the ground or exposed objects outside

- Advection frost – a collection of small ice spikes, which forms when a cold wind blows over the branches of trees, poles, and other surfaces

- Window frost – forms when a glass window is exposed to cold air outside and moist air inside.

- Rime – frost that forms quickly, usually in very cold, wet climates or in windy weather. Rime sometimes looks like solid ice.

Frost can severely damage crops. It can destroy plants or fruits. Plants with thin skins, such as tomatoes, soy, or zucchini, can be ruined. If frost is bad enough, potatoes will freeze in the ground. Farmers have had entire fields destroyed in just a few frosty nights. Frost protection measures in orchards and vineyards can be active and passive. Passive protection is widely practiced in all countries with frost problems. In reality, passive methods are often more beneficial and cost-effective than active methods. These methods include:

- Choosing sites for planting that are less prone to frost

- Planting deciduous tree and vine varieties that bloom later in the spring

- Planting deciduous crops on slopes facing away from the sun

- Selecting tolerant varieties

- Planting in protected environments (e.g. greenhouses) and transplanting after the weather warms up

- Creating physical barriers (e.g. walls and bushes) to control cold air drainage

- Minimizing or removing cover crops (e.g. grasses and weeds) between rows in tree and vine crops

- Covering row crops with plastic tunnels.

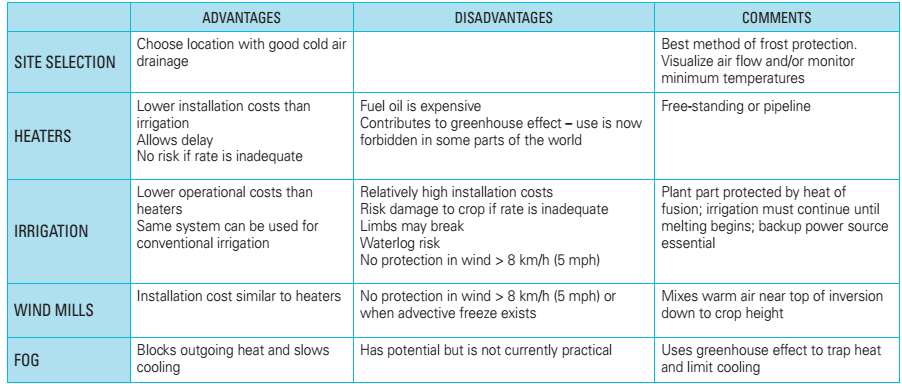

If passive methods are inadequate to provide protection, then active methods may be needed. What active methods are used for frost protection depends on a combination of weather and economic factors. Most active frost protection methods are more effective when there is a temperature inversion present. In windy locations, advection rather than radiation frosts are more likely and many protection methods provide limited protection.

Farmers have and continue to use solid-fuel and liquid-fuel heaters to combat frost on a worldwide basis; however, cost and availability of fuel has become an increasing problem over time. Today, the use of stack heaters is generally restricted to high-value crops in wealthy countries or countries with low-cost fuel sources. Because of the cost, wind machines and helicopters are also mostly used on high-value crops (e.g. citrus and wine grapes). Over-plant and under-plant sprinklers are used on a wide variety of tree, vine and row crops in many countries; however, the method is more cost-effective in arid climates where the benefits from irrigation partially pay for the expense of protecting against frost.

Advantages and disadvantages of frost protection measures