As farmers plan their growing seasons, they must juggle countless considerations: historical yields, crop rotations, soil fertility, input costs, market prices, labor needs– and the list goes on, seemingly endlessly.

The concept of “permaculture design” might be far from the mind of the busy farmer, who must walk a tightrope between economics on the one hand, agronomy on the other. And yet growers of all stripes – from small-scale vegetable gardeners to large-scale industrialized farms – can benefit from a careful consideration of permaculture principles, which provide a framework for integrating food production systems with natural systems.

Permaculture

Table of Contents

What is Permaculture?

Simply put, permaculture is a design methodology for landscapes. Permaculture aims to engineer sustainable agriculture systems which “mimic the patterns and relationships found in nature, yielding an abundance of food, fiber and energy for provision of local needs.”

The word permaculture (coined and popularized by Australia‘s Bill Mollison and David Holmgren) refers to ”permanent agriculture” – and more broadly, “permanent culture” – encompassing a whole-system approach to landscape design that champions not only perennial agricultural systems such as food forests, but also the building of self-sufficient livelihoods and strong ecological communities within these landscapes.

Despite the popularity of permaculture design courses and design manuals among gardeners, hobbyists, and the general public, large-scale farms and professional growers tend to dismiss permaculture systems as impractical, incompatible with mechanization, and inefficient due to higher labor needs and lower yields. On the other hand, permaculturists tend to view large-scale farms as ecologically unsustainable, accelerating global challenges such as pollution, biodiversity loss, and climate change.

Of course, a more environmentally and economically sustainable agriculture can be achieved by integrating concepts from both paradigms, requiring an understanding of permaculture‘s fundamental principles:

12 Principles of Permaculture

Permaculture ethics include the following commitments: care for the earth (“earth care“), care for people (“fair share“), and limits to consumption. This ethos informs how the permaculture design process unfolds, with 12 design principles providing the theoretical and practical framework for building permaculture systems:

1. Observe and interact: “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder”

Farmers are, in many ways, the ultimate observers, utilizing their senses, experiences, and knowledge to evaluate the health of their crops and natural ecosystems year after year.

Observation is the first pillar of permaculture design systems, referring to continuous study, engagement, and interaction with one’s context, as well as the integration of feedback – whether positive or negative – into a farm’s design. Observing where rainfall pools or flows across a field, what types of weeds are growing and where, and the effects of certain interventions on a crop and ecosystem are all examples of such observations. The proverb “beauty is in the eye of the beholder” best encapsulates this principle, as it suggests the biases and value judgements inherent in our observations and the need to decouple our observations from these judgements to embrace many perspectives.

2. Catch and store energy: “Make hay while the sun shines”

Food production, at its core, is sun farming. Farmers aim to maximize the amount of solar energy captured by their crops, which is stored as biomass, food, and humus.

Permaculture’s second principle – catching and storing energy— emphasizes the importance of sun farming: “making hay while the sun shines,” or maximizing photosynthesis and energy storage on the farm. Permaculturists aim to grow crops that effectively scavenge chemical energy (soil nutrients) while converting solar energy (sunlight) into timber, seeds, animal fodder, and organic matter. For this reason, permaculturists emphasize integrating perennial and tree crops such as timber or fruit trees, which add humus to the soil year after while storing energy as various usable products. Practices like planting cover crops and living mulches are also valued, as these practices maximize the photosynthetic capacity of a field and store this energy as natural capital, i.e. soil.

3. Obtain a yield: “You can’t work on an empty stomach”

The third principle – obtain a yield – encourages permaculturists to be strategic in their crop planning, prioritizing species that generate more value than they require in terms of fertility and labor. For example, selecting high-yielding staple crops (e.g. corn, potatoes, etc.), as well as low-maintenance, high-return species (e.g. medicinal herbs) is a sound energy investment. Similarly, generating a yield even on marginal soils is possible through agroforestry techniques, such as the planting of deep rooted, hardy crops for timber on marginal lands.

4. Apply self-regulation and accept feedback: “The sins of the fathers are visited on their children unto the seventh generation”

The fourth principle encourages landscape designers to embed positive and negative feedback loops within a landscape to both encourage and curtail growth as needed, steering agro-ecosystems towards self-regulation.

For example, planting a perennial pasture comprised of grasses and legumes will encourage self-regulation over time: The grasses will proliferate until limited by available nitrogen, while the nitrogen-fixing legumes will proliferate until limited by available phosphorous, with the ratio of grasses to legumes oscillating over time as nutrient availability shifts in favor of one species or the other.

The proverb “the sins of the fathers are visited on their children unto the seventh generation” is an example of how negative feedbacks like climate change and pollution are slow to emerge: The consequences of our actions aren‘t always immediately felt, instead affecting future generations or those living downstream. As such, the most sustainable systems are those with built-in feedback mechanisms which encourage self-regulation.

5. Use and value renewable resources and services: “Let nature take its course”

The fifth principle encourages farmers and permaculturists to integrate renewable resources into their operations – albeit with care. While renewable resources like solar energy are virtually inexhaustible, others forms like trees take time to regenerate, meaning they should be consumed judiciously.

Although modern farmers may find it difficult to move away from fossil fuels and agro-chemicals, they can reduce their consumption of these resources by shifting towards no-till, minimal-till, and organic production systems with lower carbon footprints. In lieu of fossil fuels, no-till farmers leverage natural processes – including the tillage and composting activity of earthworms and voles – to improve soil structure. Other farmers employ animals (for example, hogs and poultry) to stir up the soil as they dig for insects.

Renewable Sources

6. Produce no waste: “The problem is the solution”

The sixth principle encourages farmers to re-think concepts like “waste.” Creatively utilizing waste products – whether it be manure from a neighboring farm, sawdust from a local mill, or municipal waste products like biosolids, wood chips, and yard waste – can bring great value to a farm, adding organic matter to soils while acting as a mulch. Similarly, insects traditionally considered “pests” such as slugs and grasshoppers can become a food resource for livestock like ducks, while old equipment can be repaired and repurposed for new uses.

7. Design from patterns to details: “Don’t miss the forest for the trees”

The next principle – design from patterns to details – advises growers to design their permaculture farms with natural patterns in mind, including climatic patterns and ecological gradients specific to your local context. For example, knowing how native vegetation types change along a local fertility gradient can help designers select the most efficient species for their landscape and soil type; and understanding phenological patterns can help you predict and prepare for pest outbreaks.

The proverb “don’t miss the forest for the trees” reminds designers to define broad patterns and management zones first, granular details second, to avoid common pitfalls, such as selecting inappropriate vegetation for your farm or homogenously managing a heterogeneous landscape. Small-scale permaculture gardens often build natural patterns into the landscape itself, planting vegetation in spirals or web shapes, though this is not a requirement.

8. Integrate rather than segregate: “Many hands make light work”

The eighth principle highlights the importance of relationships on the farm. Studying the ecology of any landscape will quickly elucidate the complex web of interactions between the plants, animals, insects, fungi, bacteria and other organisms that coexist there. Encouraging symbioses, or mutually beneficial relationships, among different design elements on the farm should be the goal of a permaculturist or farmer, who must consider the multi-functional roles played by every creature and feature of the landscape.

For example, a tree performs countless functions within an ecosystem, not only providing food resources for different species, but also shaping the ecosystem itself by recycling soil nutrients, providing windbreaks, and creating microclimates for new species to thrive.

9. Use small and slow solutions: “The bigger they are, the harder they fall”

This principle prompts designers to consider the energetic and material limits to scale. Although some efficiencies are gained by the largest operations, larger scales can also lead to the loss of different functionalities within a landscape. According to Australian permaculturalist Bill Mollison, sustainable growth should be modeled on cellular design, with replication and diversification serving as levers for growing your operation, as opposed to than unmanaged, hasty growth.

10. Use and value diversity: “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket”

Diversity is one of the key principals of permaculture, with the adage “don’t put your eggs in one basket” underscoring the importance of diversity as a buffer against disaster, both economic and environmental. Diversity in this context refers not only to species diversity, best exemplified by biodiverse polycultures like forest gardens, but also genetic diversity within populations, which allows for adaption, as well as structural diversity within a landscape, which allows unique species niches to develop.

Farms that grow many different species and varieties have built-in crop insurance, better able to resist pest and disease outbreaks, market forces, and natural disasters than their monocropping counterparts. Of course, even permaculturists recognize the importance of balancing variety and possibility on the one hand, with power and productivity on the other.

11. Use edges and value the marginal: “Don’t think you are on the right track just because it is a well-beaten path”

The 11th principle calls our attention to the margins – the liminal spaces in a landscape where the most interesting events often take place. The borders between ecosystems – for example, successional areas between forests and grasslands; or shallow coastlines bridging land and sea– are often the most bio-diverse and productive ecosystems. Hedgerows are a classic example of this idea applied at the farm level, bridging pasture and cropland while serving as a windbreak, erosion buffer, and habitat for important predators and pollinators.

12. Creatively use and respond to change: “Vision is not seeing things as they are but as they will be.”

Change is an inevitable reality in every landscape. Whether it be large-scale, catastrophic change in the form of floods and fire, or long-term, incremental change in the form of entropy and decay, farmers and permaculturists must know how to respond to change. In a global context of climate change, the capacity of farm landscapes to weather extreme storms, natural disasters, and new dynamics of pests and pathogens will ultimately make or break a farm. Building flexibility and adaptability into a landscape is a start. Identifying predictable changes that may occur on your farm is another strong step towards building resilience in the face of unpredictable change.

What is the difference between permaculture and organic farming?

Permaculture, of course, is not the only sustainable way to farm. Organic farmers, conventional farmers, and integrated farmers alike can all steer their farm’s ecosystem towards health and productivity if equipped with the right knowledge and tools.

Permaculture and organic gardening techniques differ in several important ways. Although permaculture leverages organic principals, such as prioritizing soil health and naturally-derived inputs, permaculture systems are more likely to integrate consumer waste, polyculture plantings, and perennials than their organic counterparts.

At its core, permaculture farms leverage a design process, while organic farms leverage a certification process. Organic farming, by that token, offers growers greater opportunities to scale their production, while guaranteeing organic growers premium prices on the market via the USDA’s certified-organic label.

Permaculture and digital farm management

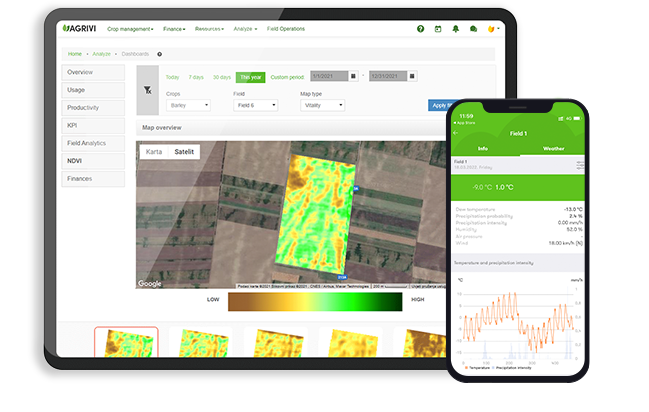

Although managing permaculture farms digitally may at first seem counterintuitive, digital tools like AGRIVI provide permaculturists with a sound method for recordkeeping, budgeting, input management, productivity tracking, and farm planning.

The ethics and principles of permaculture align with the sustainability-centric goals of Farm Management Software — namely, to track every energy expenditure, every labor-hour, every gallon of irrigation water spent on the farm towards a more efficient, sustainable agriculture system. Permaculture farms are not unlike conventional farms in their need for strong resource planning and accounting software, which can be seamlessly integrated with AGRIVI‘s open-API platform.

Given the complexity and species richness of permaculture farms, moreover, a crop-agnostic tool like AGRIVI is perfect to simplify season planning. Localized and customizable databases of pests and diseases — not to mention satellite imagery and vegetative indices — can further illuminate crop health in real time, equipping you with actionable insights for your farm.